VW W30 prototype from 1936

World premiere on the racetrack

The history of this prototype is virtually unparalleled in the automotive world. We are pleased to recount it here with the kind permission of AutoBild.

The history of this prototype is virtually unparalleled in the automotive world. We are pleased to recount it here with the kind permission of AutoBild.

Important information for all fans of mobility and Classic Days at Rittergut Birkhof:

The VW from the W30 test series with chassis number 26 will be coming to Classic Days 2025. We are delighted to be able to show the car as an exhibit, but also to be able to officially drive it for the first time ever. In a special run to mark ‘80 years of the VW Beetle’ as a civilian vehicle and a means of mobility for many after 1945, we will be showing the prototype on the Racing Legends circuit from 1 to 3 August 2025.

And here is the story behind the W30:

Germany in autumn 1936:

From October to December, a new type of rounded car travels across the country on country roads and motorways. It is the prototype for a test car designed to determine what an affordable car for the people should look like. It covers 50,000 kilometres – with success, as the concept seems to be working.

So the designers built a test series of 30 modified cars and called them W30 – the precursor to the later VW Beetle. In 1937, the cars were tested for reliability, ‘motorway stability’ and durability. The precursors to the later KdF car had to cover 2.4 million kilometres, and everything was documented. This was probably the first time anywhere in the world that a new car had been tested so extensively. The test cars were then completely destroyed – or so it is said. Nevertheless, a curious Beetle chassis was found at a parts collector’s in Austria.

Austria 1998:

VW employee and Beetle expert Björn Schewe from Wolfsburg is, as so often, on the road to find and buy old Volkswagen parts. Schewe has a good network, and this time his destination is a car and parts collector in Styria, 900 kilometres away. He shows Schewe his rarities. Schewe recounts: ‘He then led me outside, where he had set aside his unique parts and curiosities.’ One of these curiosities is a chassis standing upright against the wall that looks like it belongs to a Beetle, but somehow doesn’t.

The collector explains that the part comes from a car in the W30 test series. That would make it the oldest surviving vehicle part in VW history! Schewe immediately recognises its historical significance: ‘I was blown away by the collection and felt like I was suffering from jet lag, but the chassis was sacred – I envied him. Unfortunately, there was no way he would part with it.’ Schewe immediately informs his good friend Christian Grundmann in Hessisch Oldendorf, also a VW expert and, together with his father Traugott, owner of the famous Grundmann collection.

Both try to acquire the chassis, repeatedly and unsuccessfully. Nevertheless, a good friendship develops over the years with the collector in Styria, and Schewe visits the man again and again. At some point, the collector realises that it would take him ‘several centuries to restore all his projects’ and decides to sell part of his collection. This includes the chassis! However, he only agreed to part with it in exchange for an unrestored Schwimmwagen and other items.

Schewe uses a 7.5-tonne lorry to collect everything he can get his hands on for Grundmann, including the chassis, of course. In Hessisch Oldendorf, the piece is first inspected, then sandblasted and primed. To the amazement of Schewe and the Grundmanns, the embossed number ‘26’ appears – they all agree: this must be car 26 from the W30 series. The three cannot prove it beyond doubt, but they are certain. There are clear structural features, says Christian Grundmann: ‘The shape of the frame head only existed on the W30.’

But how could the frame survive when all the cars were supposedly destroyed? Grundmann explains: “The chassis was preserved because it was also used for prototype testing of the VW Type 82 Kübelwagen, which was often done. The other chassis were destroyed, but this was more for public consumption. The Kübel ended up in a forest near Gmünd in Carinthia (where Ferdinand Porsche moved in 1944). What remained of the Kübel ended up in a scrap yard and was rescued from there in the 1960s.

Grundmann’s initial idea:

The chassis should go where it belongs, namely to VW. There, a company commissioned by the Volkswagen AutoMuseum Foundation has been working on a replica of the W30 for some time. However, construction is too far advanced to incorporate the valuable part – VW refuses. Years later, in 2002, an ambitious plan takes shape: father and son Grundmann want to restore the car with the number 26. A difficult undertaking, as neither a real model nor a reference vehicle are available. However, there are some drawings, historical photos and the replica at VW.

But that only helps to a very limited extent. ‘The replica is quite good in itself,’ explains Christian Grundmann. The first goal: a rolling chassis. ‘We have organised a lot of KdF material, most of it in the former GDR,’ says Schewe. Until then, the Grundmanns are keeping the project secret: ‘We didn’t want to go public with it until there was something to see, it had to represent something.’ First, they reconstruct the missing floor panels, press them from whole pieces and weld them to the frame. The engine that is now being used dates from 1939 and has 23.5 hp, one and a half more than the original. Grundmann wants to have the gearbox shells recast, but the inner workings will be from a more recent era – whereby ‘newer’ here means 1939.

The main problem is reproducing the sophisticated shape of the bodywork. To tackle this task, the Grundmanns recruit Andreas Mindt, former head of exterior design at Audi and now head of design at Bentley. He begins drawing on a white wall using graph paper on a scale of one to one, just like the designers did in the 1930s. Mindt thus creates a valuable foundation. Once the plans were roughly in place, it was time to start building. Christian Grundmann: ‘At first, we considered doing it in our own workshop, but that wasn’t possible. We needed a partner who was familiar with the 1930s.’ Grundmann sent out enquiries nationwide, but with only moderate success. It was only when someone suggested contacting René Große in Wusterwitz, Brandenburg, that progress was made.

The business is a perfect match, because Große is a professional when it comes to 1930s cars. Once Traugott Grundmann and Große discover they have things in common, the decision is made. ‘Go ahead,’ says Grundmann, giving the go-ahead. Große drives to Hessisch Oldendorf, first takes a tour of the Grundmann collection and then looks at the floor assembly and his new task: ‘This is something special, especially its history. It’s a big piece of German contemporary history. You can feel the enthusiasm of the Grundmanns, who live and breathe VW.’

Over lunch, they agree on the details, and the floor assembly is transported to Wusterwitz a few days later. ‘First,’ says Große, ‘we analysed the drawings and got an overview of the dimensions.’ Next step: turn two dimensions into three. From his many collaborations, Große knows a model maker in Berlin who creates a 3D model on the computer based on photos, drawings and dimensions. The lines, windows, proportions and more are compared again and again, a process that takes two whole months. Große and his team then produce a cutaway model from the computer graphics. But even that is not always the optimal solution. Große: ‘There were problems in certain areas; the curve of the bonnet, for example, didn’t look good.’

When transferring this to practice, corrections and comparisons are made repeatedly, and then it’s finally time to get to work: ‘A package arrived with paper cutting templates. These were transferred to wood and sawn out. This creates three longitudinal frames in the shape of the W30 and more than 30 cross frames, which are inserted at intervals of 100 millimetres.’ This step takes a total of around 100 hours. The space between the frames is filled with hard foam to create a smooth shape. Sheet metal is placed on the wood. Große explains: “The body is divided into manageable sheet metal segments, each measuring a maximum of one square metre. Now you place paper on the model and see where the sheet metal needs to be stretched when tensioned and compressed when wrinkled.” About 40 sheets of metal have to be cut to size, adjusted, hammered and cut again for the bodywork. Then it is welded, autogenously and butt-welded, just like in the old days, then sanded and corrected again and again.

Unexpected difficulties nevertheless arise. ‘The exterior design had already been finalised,’ explains Große, ‘when the spare wheel was delivered and didn’t fit in the front. We all wondered whether they even had a tyre on the spare wheel back then. There are pictures where only the rim is visible.’ The mudguards are created using the same procedure, over a mesh of sturdy wire. After production, the challenging doors are fitted with the inner workings for the crank windows. ‘We used the window regulator mechanism from the rear doors of a Mercedes W 136, which, according to the old photos, should correspond to the original,’ says Traugott Grundmann.

The original Mercedes 170 locks and door handles have also been installed. The brake drums, axles and wheels come from a pre-war Beetle. The steering wheel comes from a 1938 prototype. Grundmann wants to use original or reproduced parts wherever possible. The seats are also being reconstructed based on photographs, and the fittings come from pre-war series production, just as they were used back then. The headlights are proving difficult. Traugott Grundmann: ‘We needed a lens with a diameter of 170 mm and searched for ages. We finally found what we were looking for in pre-war motorcycles. We discovered the right reflectors in a VW Karmann.’

One problem will be the colour scheme, as there are no templates available for this either. The Grundmanns are trying to use a computer to determine the colour tone from the grey tones in the photos. One thing is certain, however: it will be a shade of grey that most closely matches the original. The paint itself will be nitrocellulose lacquer, just like it was back then.

Große adds: ‘The paintwork mustn’t be too perfect in terms of the smoothness of the bodywork; back then, the surface was also a little rougher.’ Once the W30 has been painted, it should be ready in spring 2022 after almost two years of construction. Will this oldest piece of VW history then also be on display at meetings? ‘Of course,’ says Grundmann, ‘it should be ready to drive and pass its MOT!’

The idea of an affordable car for the people was not new, and various designers had already tried their hand at it. Ferdinand Porsche was one of them: he had already designed the Volkswagen in 1933, which he presented to the National Socialist Reich Ministry of Transport in January 1934 in his exposé on the construction of a German people’s car. In 1934, Porsche received the contract from the RDA (Reich Association of the Automotive Industry) to design and build the Volkswagen. The V1 to V3 test cars were assembled in the garage of Porsche’s home, after which a series of 30 prototypes, the Test Car 30, was produced.

They were built at the Daimler-Benz factory in Sindelfingen and tested over approximately 2.4 million kilometres at a cost of 1.7 million Reichsmarks. A vertical window behind the rear seats and slits in the bonnet allowed the driver to see behind the car. The KdF car was ultimately developed on the basis of the W30. Initially, it was to be built jointly by all German car manufacturers, but in 1936 the Nazis decided to establish an independent Volkswagen factory.

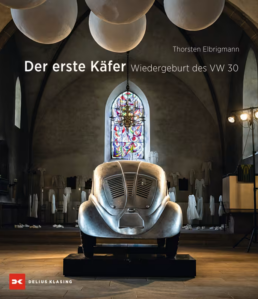

We also recommend the book about the story, published by Delius Klasing:

Der erste Käfer – Wiedergeburt des VW 30 (The First Beetle – Rebirth of the VW 30) by Thorsten Elbrigmann.

https://shop.delius-klasing.de/der-erste-kaefer-p-2001943/